Martin at Aardvarchaeology posted some excellent questions regarding my brief comparison of Swedish and American heritage preservation laws. Here's my attempt at some answers:

From Martin:

What happens if a member of the public makes a clearly prehistoric find on federally owned land, without digging or damaging anything, and alerts the local authorities? For instance, a collection of lithics from the erosion slope of a stream gully or the edge of a quarry. (I'm sure he or she would not be held in error.) Who owns such finds?

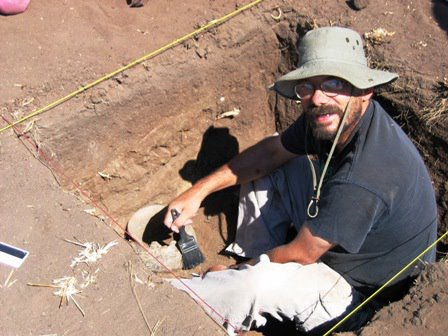

Excellent question and it reminds me that I was remiss in explaining something important about the law and its consequences. I can tell you that most of us with adminstrative responsibility for historic preservation would not be prosecuting someone who found something and brought it in to our attention (I say most only because there are probably one or two exceptions out there in the larger cultural resource management world). I am personally very greatful when someone alerts me to a site or artifact they've found. I try to believe that most people collect these things because they have an interest: if I can steer that interest away from casual collecting and into something less destructive, I try to take that tact: I'll go out to the site with them; enlist their help to record the site or catalog the artifacts, etc. I do believe education is our best defense against systematic looting. I think we gain more by working with the public rather than lecturing them. I would still prefer it if folks didn't actually pick up anything and just alerted me or someone else to the area's location. Still, I'm not going to slap the cuffs on if you happen to bring something in! We try to save the ARPA prosecutions for people digging or systematically stripping a site.

To this end, the Forest Service specifically has a program called Passport In Time that offers volunteer opportunities for people interested in archaeology or other aspects of historic preservation to work side-by-side with professional archaeologists. In this way members of the public can participate, feel a sense of contribution, and hopefully understand why we archaeologists get a little anal retentive regarding artifact collections from sites. There are other programs in other agencies and often we just look for local volunteers to help us with something without going through a formal program.

Nonetheless, in answer to Martin's question: the artifact is still considered government property and the person would have to turn it over to officials.

What percentage of interesting sites are on federally owned land? E.g., how many of the known Moundbilder mounds? In other words, is the federal legislation relevant in the greater number of cases? Or is it simply a question of trespassing laws keeping archaeological surveyors off privately owned land, so that such land forms white spots on the distribution maps?

Very good question, and one that's not easily answered. Out west, where most of the broader tracts of federal land are located, we probably have a significant number of the known sites on public land. However, there are still lots of those "white spots" (and yes, they really are white on many of our maps) where we have private or state land. Many private areas as you might imagine also have significant sites, however, largely because many of those places were homesteaded or deeded over many generations and tend to occur on the same locations that many Native Americans found attractive. Interesting that you should mention the Moundbuilders: I actually worked for the Burial Sites Preservation Office in Wisconsin in the 1980s and early 90s and we were tasked with preserving many of the mound locations (largely because they were shown in most cases to contain burials). I'm taxing my memory somewhat, but I believe the site protection legislation that passed the Wisconsin state assembly in 1987 specifically protected mounds, even on private property. So again, the short answer to Martin's question is that "it depends". Some communities and states have excellent preservation laws in place (particularly those in the east, where there is less federal land and historic preservation has traditionally fallen to the states and local communities) - others do not.

In regards to "interesting sites": I'm assuming we're talking about important sites that might contribute something of value (data, uniqueness, documentation of significant event, etc.). In the U.S. these would be sites eligible for the National Register. We've found approximately 20% of the sites we formally evaluate are eligible for the National Register. This figure might be skewed somewhat, given that we tend to formally evaluate smaller sites that aren't likely to be considered eligible anyway. This leads me to a question for Martin, however: it sounds as though Sweden's National Heritage Board is roughly equivalent to our National Register of Historic Places...are all sites in Sweden automatically registered with the Heritage Board once identified, or is there a similar "evaluation" process to determine if a site is eligble for registration?

My post didn't say much about sites and land development. Does the US evaluation of an area in advance of e.g. a road development differ with regard to who owns the land? Can the authorities force private land owners to admit archaeologists for surveying in such a case? In Sweden, a road or gas pipeline development will usually operate with a wide corridor of potential placement in the early stages of the project, and then the final placement within the corridor will be influenced by the results of archaeological and biodiversity evaluations. Which of course cover the entire corridor regardless of who happens to own the land.

The short answer to both questions is "yes", although again "it depends". Most projects tend to be either federally or state funded. If federally funded (in any amount) the project must comply with NHPA, so archaeologists must be allowed to survey and if necessary evaluate and mitigate before the project can proceed, even if through private property. State laws again vary, but here in Calilfornia, generally the same thing applies. CEQA (California Environmental Quality Act) laws require some degree of historic preservation compliance similar to those at the federal level, although I'm not thoroughly familiar with all the regulations at the state level (being federal, if we're involved at all our processes and procedures generally supercede everyone else so I haven't had the need to be completely up to speed on state and local laws!). Afarensis and Carl might be able to wade in here on their perspectives for the situations in Missouri and Texas.

At the local (generally county or city) level of government, the stipulations again vary widely across the states, but most seem to have some kind of protection for historic resources. Generally this occurs via the permitting process. In many places you can't get a permit to put that 2000 square foot garage up until you've had the area cleared by a professional archaeologist.

On the planning end for bigger projects, it sounds like Sweden and the U.S. are somewhat similar. Our planning efforts fall under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) which includes provisions for considering all kinds of issues: water, wildlife, economic, fisheries, botany, and of course...historic resources. We generally try to plan projects within the context of understanding where all the potentially affected resources might be so before project implementation so that there's little need to suddenly change project plans when we sudenly find that the only habitat in the state for the red breasted doodle bug is right in road path. If we do the planning correctly, the hypothetical situation with the Giza pyramid I noted previously should rarely happen.

Did I understand correctly, that a US landowner may dig or dynamite any site on his land as long as it doesn't contain graves? Scareee!

I'm not entirely up on the laws governing private property and I'm sure again, "it depends", but yeah, that's pretty much my understanding. Bear in mind, however, that unless he's just throwing sticks of dynamite for something to do after church on Sunday, he's probably engaged in digging or blowing something up for some kind of permitted project (via county, state or feds). As such, he's most likely needed to have archaeologists conducting survey and raising awareness of any sites that might be located in harm's way.

Again, excellent questions! Hopefully I've gone some distance toward answering them, but I'm more than willing to entertain follow-ups.

Don't forget everyone: Aardvarchaeology is hosting the next edition of Four Stone Hearth - get your submissions in!!

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

3 comments:

Excellent answers! Here's coming back atcha.

"it sounds as though Sweden's National Heritage Board is roughly equivalent to our National Register of Historic Places..."

As I work at the Swedish NHB I thought I´d jump in to explain that the National Heritage Board does keep both an Archaeological Sites Information System and a Register of Built Environments, but this is only one aspect of the Board´s duties and is run by one unit comprising about 5% of our total staff. The NHB is more akin to a cross of your Advisory Council on Historic Preservation and National Park Services I believe.

Both the information systems mentioned above are available on-line, e.g. check out this link to all registered labyrinth sites in Sweden:

http://www.kms.raa.se/cocoon/fmis-public/objektlista?remnantType=11105&

Click the "Visa i Google Earth"-link to see the distribution pattern of this monument type.

Cheers,

David Haskiya

David,

Thanks for the clarification! If the NHB is more like our ACHP then my hat is off to you: you guys have a heck of a job to do! Thanks again!

All the best,

Chris

Post a Comment