Earlier this month, the great new blog Aardvarchaeology (Martin Rundkvist) posted a discussion of preservation issues in Sweden that got me to thinking further about the state of preservation law in the U.S. Martin suggests that to his knowledge Sweden may have the strongest legal protection for sites and finds in the world. That may be the case – some of the provisions of Swedish law as Martin describes them would definitely enhance archaeological site protection here if implemented.

So what does American law say? Well, to quote the guru of cultural resource preservation law in the U.S., Thomas King, the initial answer has to be: “it depends”. Unfortunately the American penchant for letting no legal vacuum go unfilled has created a sometimes bewildering array of laws, statutes, regulations and policy regarding historic preservation in this country. Martin’s post on Swedish antiquities law starts with a very simple (and here, frequently asked) question: who owns an archaeological find made by a member of the public? Martin indicates that in Sweden, the important legal relationship is between the authorities and the finder, not the landowner, in large part apparently because there are no trespassing laws in Sweden (a totally alien concept here in the states). At a certain level, the same applies here in America.

In the U.S., historic preservation on public lands (Forest Service, BLM, National Park Service, Reclamation, Fish and Wildlife – any lands owned by the federal government) is governed by federal laws, most prominently the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) and the Archaeological Resources Protection Act (ARPA). Note that these two laws are the most frequently implemented, but there are a host of other laws that protect cultural resources: American Antiquities Act, Abandoned Shipwrecks Act, Historic Sites Act, American Battlefields Protection Act; there are even some statutes in the Internal Revenue Code and Department of Transportation Act that have a bearing on historic preservation. The National Park Service website has an updated list of federal laws that govern cultural resources: at last count over 50 federal laws exist that touch issues of historic preservation in some way.

So in answer to Martin’s question regarding whether or not a member of the public can collect artifacts or excavate sites on federal (publicly owned) land, the answer is absolutely not. Members of the public not legally authorized to collect or excavate are considered in violation of any of a number of laws (ARPA being the primary one) and can be prosecuted with fines, jail time or both. Those of us charged with protecting archaeological resources on public land spend a good deal of time trying to prevent the illegal collection of artifacts, usually through a two-pronged approach: educating the public on the need to protect cultural resources and vigorously prosecuting those who fail to heed the educational message.

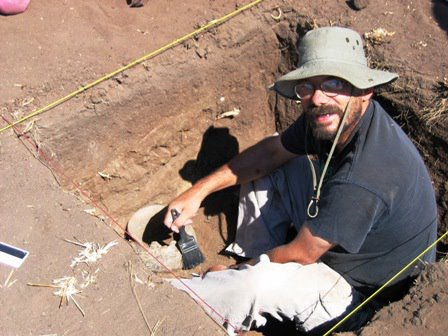

It is principally ARPA that regulates excavation and collection on public lands. Under this statute, the government may issue excavation permits for those with legitimate interest and expertise (usually professional archaeologists interested in research) to conduct archaeological excavations on public lands. The regulations regarding who may or may not excavate are clear. In this context I have always found it amusing that Carl Baugh, Willie Dye, Richard Fales and several other creationist “researchers” claim status as archaeologists or paleontologists, yet none would ever be issued an excavation permit under ARPA. They all lack legitimate credentials, education and experience necessary to be considered the principle investigator or director of an archaeological excavation on public lands in the U.S.

ARPA clearly prohibits excavation of archaeological resources on federal land. However, there are those who believe that ARPA maintains an exception for the casual collection of arrowheads and historic things not over 100 years old from surface contexts. The provision of ARPA specifically reads as follows:

…No item shall be treated as an archaeological resource under regulations under this paragraph unless such item is at least 100 years of age (16 U.S.C. § 470bb(1)).

And then later…

Nothing in subsection (d) of this section shall be deemed applicable to any person with respect to the removal of arrowheads located on the surface of the ground (16 U.S.C. § 470ee(g)).

I know of some folks who carry a copy of ARPA with them when the collect arrowheads or historic bottles believing that the so-called “arrowhead exception” will protect them from prosecution as long as they’re not digging. They are in for a shock if they ever get caught. In 1996 the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals upheld a conviction by a lower court ruling against a defendant claiming rights to collect under the “less than 100 years” and arrowhead exceptions in ARPA. Basically the court found that even though the law does not specifically deal with artifacts falling within those categories for prosecution under ARPA, the law does not specifically assume “transfer of rights” for those items when found. The court further emphasized that the government did not intend to allow for collection of these items from archaeological contexts of any kind, surface or otherwise. Finally, the court pointed out that even if such were not the case, ARPA specifically notes that other statutes allow for the government to prosecute for collecting artifacts of any type in any archaeological context (surface or otherwise):

This exception is not intended to encourage removal of arrowheads from public lands, butrather to exempt such removal from the civil and criminal penaltyprovisions of the ARPA. See 16 U.S.C. § 470ff(a)(3); 36 C.F.R. §296.3(a)(3)(iii)…Also, the ARPA expressly provides that the removal of arrowheads can be penalized under other regulations or statutes. See, e.g., 49 Fed. Reg. 1016, 1018 ("regulations under other authority which penalize [the removal of surface arrowheads] remain effective.").

The clear message is that no member of the public can excavate on public land without a permit (and the requirements for granting those are explicit); nor can they collect artifacts of any kind. Other public lands (state, county, municipality, etc.) are governed by a dizzying array of state and local laws as you might imagine – some more lax than others. In general, those state regulations of which I am aware tend to follow the federal lead and prohibit or severely restrict artifact collecting and archaeological excavation.

However, Martin’s question regarded the collection on private land. Of course, in the U.S. trespassing laws come into effect and you can’t just walk on to anyone’s land and start collecting without permission. Assuming permission or you’re the landowner, however, there are very few regulations preventing you from collecting antiquities on your own property. Generally excavating or “robbing” burials is the exception. [The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) has spawned a series of state and local statutes regarding the protection of human burials (including non-Native American in some cases). This has become another major law at the federal level (which I have to deal with on a frequent basis in my capacity as Forest Archaeologist) but it is also having effects at other levels. See Afarensis’ series of excellent posts on the issues regarding Kennewick – this was a major NAGPRA issue]. It looks like collection on private land in the U.S. is significantly different from the case in Sweden. Martin reports:

…let me also emphasise that the landowner has very few rights with regard to the sites on his land. They sit on his property, but they are themselves in many ways property of the state. He can't dig them, he doesn't own any finds from them, he is forbidden to change his current agricultural methods on the sites for something more destructive.

This is clearly not the case in the U.S. With few exceptions, the landowner effectively owns the site and its contents. I’m not as certain with regard to the sale of artifacts in the U.S., if obtained legally, but illegally obtained artifacts are prohibited from sale under ARPA. There are other interstate commerce clauses that may also come into effect here.

Apparently, the Swedish rules cited above apply to multiple artifacts coming from a single location. Individual artifacts recovered in isolation fall under different rules depending on the level of precious metal content. In effect, the Swedish landowner doesn’t own complete sites and their contents, but they and other members of the public may be allowed to own isolated artifacts under some circumstances.

In this regard, I would have to agree with Martin and suggest that the preservation laws in Sweden (at least for private property owners) are better than those here. Given Martin’s brief discussion, I think would go so far as to say that if I had the power, I would gladly consider an “isolated artifact” exception (even perhaps on federal land) in exchange for government ownership of all archaeological sites and their contents on all lands, including private. Public interest in historic preservation would be better protected if cultural resource sites could not be considered private property.

One thing Martin alludes to but doesn’t discuss in depth is protection of cultural resources during “project” implementation (road/building construction, timber harvesting, livestock grazing, etc.). For those of us responsible for the protection of cultural resources on public land in the U.S. this is about 95% of our job: ensuring that “undertakings” don’t adversely affect historic properties. Our guiding legislation in this regard is the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA). NHPA is complex and its implementing regulations are contained in the Code of Federal Regulations 18 CFR 800, specifically in reference to Section 106. Whole classes are taught on Section 106 of the NHPA and its implementing regulations but basically it boils down to this: before an undertaking can take place, the effect of that undertaking on historic properties must be considered. This assumes several things. First, you have to know if any historic properties exist within the project area, so you have to find any sites that might exist. This typically means some kind of survey is required (not necessarily a typical intensive archaeological survey either, but that’s a different issue). Secondly, you have to determine if these sites are important. “Historic property” actually has specific meaning under the regulations: it’s a site that has been determined eligible for the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP). This might be similar to Sweden’s National Heritage Board. Whether a site is eligible for NRHP listing or not is usually determined through formal evaluation of the site. Finally, if a site is determined eligible, any adverse effects from the undertaking have to be determined and mitigated if they cannot be avoided.

The whole process is complex. The regulations largely discuss how sites are to be located, evaluation procedures, determinations of effect, and potential mitigations. A couple things of general interest: It is often assumed that this regulation “protects” historic properties. Legally it does no such thing. All the law requires is that we “take into consideration” the effects of a project on the resource. Let’s say we’ve done our survey and located the Giza pyramid in the middle of our planned road construction route. Ok, it’s clearly an eligible property (it’s unique, meets certain criteria, has the potential to add to our understanding of prehistory or history, etc.). So what do we do? Well, the road is planned to go right through it, so clearly our project will have an “adverse” effect to the pyramid. The easiest “mitigation” would be to avoid impacting the site and re-route the road. But let’s say we can’t. Can we still put the road through? Yes. We would have to meet with a bunch of interested parties and decide a course of action: we could dismantle the whole thing and rebuild it somewhere else; we could just excavate the hell out of it and recover as much information as possible; we could document the whole thing with photos, drawings, etc. Once we agreed on a course of action and completed what we all agreed to do, the bulldozers could go forth. Legally, the pyramid will not stop the road. I emphasize legally, because there are other considerations that obviously come into play: economic and public opinion/political. Clearly a lot of people are probably going to be upset over the destruction of the Giza pyramid and they will bring pressure to bear on those who want to put the road through. Also, all of those mitigation measures cited above are extremely costly, and it may be more economically feasible to move the road rather than bear the cost of mitigation. In fact, generally archaeological sites are “protected” on federal land in this manner: it’s easier economically to just change the project design.

Again, regulations at the state and local levels vary widely, but these also seem to follow the primary goals of federal legislation. When we turn to private land, the situation is different and does not appear to follow the Swedish pattern. Martin notes that the farmer in Sweden:

…is forbidden to change his current agricultural methods on the sites for something more destructive.

In the U.S. the farmer can pretty much do what they want. There are a couple of exceptions, however. On the local level, county planning usually requires identification of cultural resources on the landowner’s property before they will issue a building, land exchange, parcel split or other permit. Again, this varies considerably across the country.

A private landowner may also be required to comply with NHPA regulations if he receives any sort of federal funding for his project. Federal grants for vegetation management around wildland/urban interfaces, for example, require NHPA compliance before the money can be released. This is what we call the “federal handle”…the project may not actually be located on federal land, but if it is being even partly financed with federal dollars, then NHPA (and other) regulations apply.

I’m not sure how these regulations stack up against those in Sweden (and they are far more complex than I have discussed here - even with regards to private property). It is clear, however, that regulations such as these have gone a long way toward protecting cultural resources around the world. More stringent applications certainly wouldn’t hurt and we might follow Sweden's lead in this regard.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

6 comments:

Many thanks for your kind words, and for an extremely interesting entry! Here's a reply with loads of questions.

Martin,

I left a comment on your blog; I'll try to answer your excellent questions and post them here shortly. Thanks! (and great blog! Everyone should check out Aardvarchaeology!).

If you feel like dwelling in legal text a little more, here's Finland's take on the issue

http://www.nba.fi/en/antiquitiesact

-Aino

thank you this is very helpful article

Very useful piece of writing, much thanks for your post.

Thanks so much for the post, really effective data.

Post a Comment